InterACTWEL

A key to resilient food, energy, and water sectors in local communities

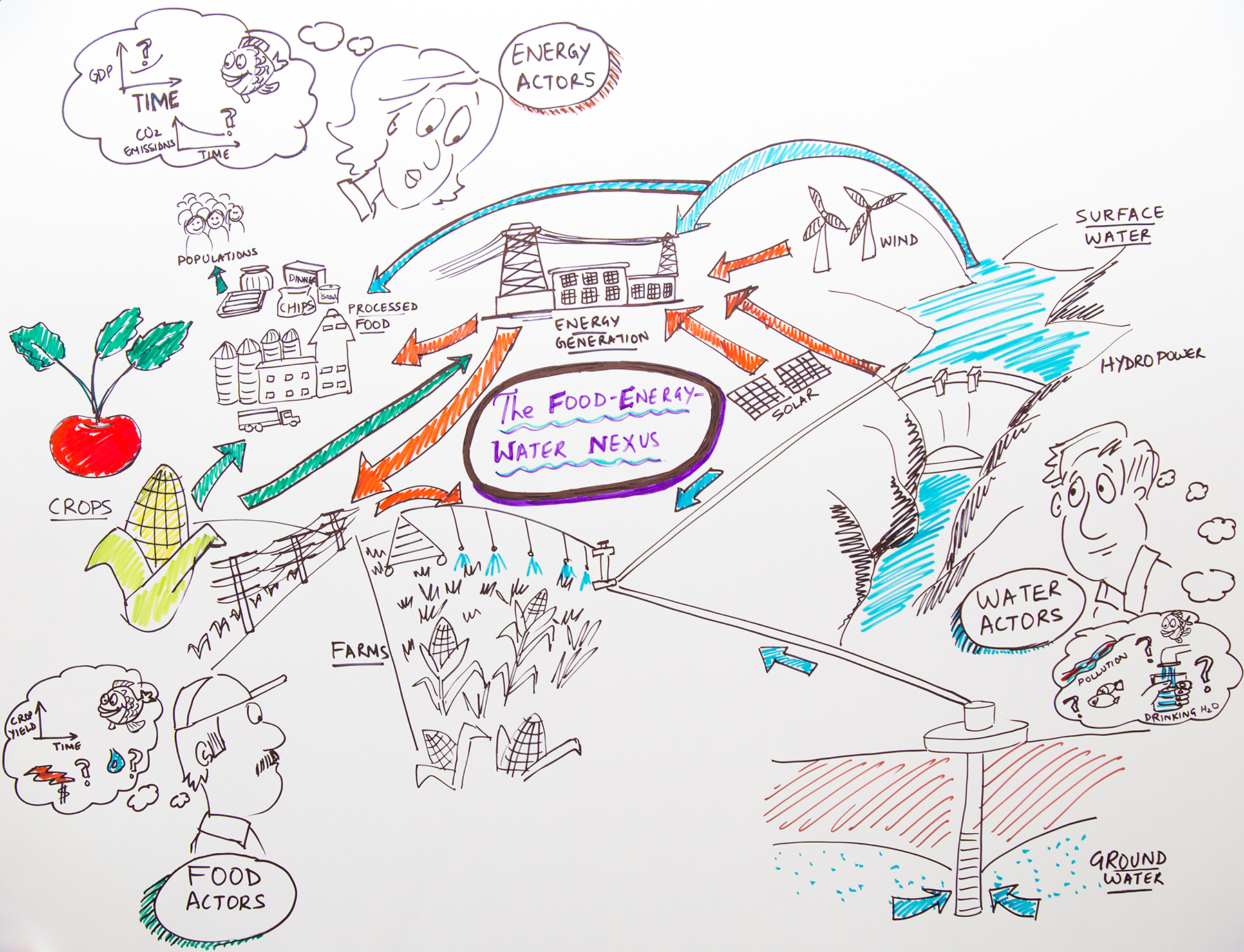

Food, Energy, Water NEXUS

Our planet’s natural resources, such as water, land, atmosphere, and ecosystems, face an increasing amount of stress from a wide range of disturbances. These disturbances may be “chronic”--meaning that they occur over a long periods of time, or they can be “shocks” that occur rapidly and with great effect. The disturbances can lead to an extensive degradation and depletion of critical natural resources. Examples of chronic and shock disturbances include climate change, floods, droughts, storms, diseases, fires, earthquakes, tsunamis, as well as disturbances caused by human activities, such as introduction of invasive species, forest clearing, acts of terrorism, and sometimes even new laws and policies. Many sectors, including the agriculture sector, the water sector, and the energy sector, heavily depend on these natural resources for economic growth, and are, as result, vulnerable to profound consequences when natural resources are stressed.

More and more communities are beginning to realize the natural resource decisions have worked in the past, no longer work for current and future resource problems because of the increasing interdependencies between food, energy, and water Sectors.

When faced with highly stressed natural resources, many communities worry about how much water they will have to grow next year’s crop up or fish habitat or how much and how expensive the energy will be to irrigate fields or power local industries. To be resilient to stresses from a changing world the agriculture, energy, and water sectors can no longer just focus on their individual use and management of critical natural resources.

They need to become aware and many of them already are that interdependencies between food, water, and energy resources that impact their communities. Becoming aware of this Food, Energy, and Water NEXUS is only the first step. We need a comprehensive set of management solutions that are flexible to the demand of food, energy, and water resource users, manager, and consumers. These solutions must have multiple flexible options for food, energy, and water for adaptable and sustainable long-term management.

What this really means is that effectively responding and recovering from both chronic and shock disturbances requires significant coordination and communication between all affected stakeholders. Without effective coordination, communities are vulnerable to inconsistent responses to change where one group may react to a disturbance in a way that only benefits their specific group such as pumping more ground water when surface water is limited without thinking of the ripple effects that may have on all other groups such as municipal users. This may lead to unanticipated risks

To explore the success of the working in nexus space, we went to Hermiston Oregon which is small town in eastern Oregon.

Hermiston Region

Hermiston Oregon is located in North East of Oregon and it is part of Umatilla and Morrow Counties. The area has population of approximately 87,700 (11,000 in Morrow County and 76,500 in Umatilla County) with largest population centers located in Umatilla County with the city of Hermiston (18,000) and city of Pendleton (17,000). The basin has a moderate temperate climate with an average temperature of 53.15oF (65.8oF max, 40.5oF min.) with raining winters, averaging an annual precipitation of 10.4 in.

Agricultural land use, including food processors dominate the Umatilla Basin with approximately 60% of land use in crops and another 30% in pastureland (Census of Agriculture, 2012). Other primary land uses include large tracts of publicly owned land, including the Umatilla Weapons Depot (DOE), Navy Bombing Range and new private sector industries, most notably data centers or “Server Farms.” These data centers hold high-power servers for private companies are increasing in size and number in the basin due to access to abundant water resources needed cool servers and a relatively inexpensive energy supply.

The Hermiston Oregon region has been growing quite a bit as a community and economy but is not bumping it up against some of the resource constraints that it has in terms of energy, water, labor, and it is perhaps a little bit more vulnerable to changes in the environment and global economic markets that it might have been in decades past and so it is perhaps time to take a more deliberative approach to long term planning, thinking about how some of those changes could affect the interdependencies of the food, energy, and water and ways that the communities can make long term plans to act together to avoid or minimize any kind of disruptions from those changes.

Umatilla River Basin problems

In 1990 DEQ declared the Lower Umatilla Basin a Groundwater Management Area because nitrate-nitrogen concentrations in many area groundwater samples exceed the drinking water standards for nitrate (10 mg/l). The groundwater area covers the lower portions of the Umatilla and Willow Creek drainages. There is a Pesticide Stewardship Partnership in the Oregon portion of the Walla Walla River drainage

Food Sector

The major economic engine of the Umatilla Basin is the agricultural industry. Currently agricultural production covers approximately 73% of land in Morrow and Umatilla Counties (USDA, 2012). Irrigated crops take up 6% of cropland in Morrow County and 11% in Umatilla County with intensive agriculture growing in size and extent (USDA, 2012). The market value of crops per farm is $1,416,736 in Morrow County with total sales $194,871,000; and the market value of crops per farm in Umatilla County is $264,088 with total sales $371,988,000) (USDA, 2012). The major agricultural products in the region include wheat, cash crops and dairy and cattle production with increasing crop land devoted to orchards (USDA, 2012).In 2008, Umatilla County had the second highest agricultural sales among the 36 Oregon counties, behind Marion County (Ibid.). Umatilla/Hermiston and Milton-Freewater primarily produce irrigated agricultural crops. Umatilla/Hermiston produces more than ninety percent of the Field Crops (potatoes, mint, etc.) and Grasses and Legumes in the County. Milton-Freewater produces more than ninety percent of the Tree Fruit and Nuts in the County. Pilot Rock/Pendleton has the highest sales of Grains (44.71%) and Livestock (43.55%) in the County. crops (e.g. potatoes, green peas, asparagus, melons), hay and silage feeds (e.g. alfalfa, corn, pea vines), fruit products (e.g. apples, cherries, prunes, peaches, apricots, grapes), and an extensive livestock industry raising cattle and calves, hogs and pigs, sheep and lambs, and chickens and turkeys. Besides being the largest industry in this county and second largest industry in Oregon, agriculture creates a rural atmosphere greatly desired by many city, rural, and regional people. A comprehensive plan considers agriculture as an irreplaceable natural resource. Its wise use is of as much importance as other resources.

Energy Sector

Energy sources in this region include, solar, wind, biofuels, coal and natural gas power plant and hydropower.

The most dominant energy source is hydroelectric power generated from the McNary Dam (980 MW) on the Columbia River. This hydropower is managed through the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) and distributed to users primarily through for-profit and non-profit energy providers, including the Umatilla Electric Cooperative (UEC). The UEC and other energy providers, such as Pacific Power provide wind (545 MW), solar (75 MW), natural gas (900 MW) energy to users in the region. Energy supply and demand are influenced by several climatic factors including seasonality and localized weather conditions, as well as state and federal policies.

Water Sector

Water is hugely contentious in the state of Oregon and this region unsuccessfully for many years tried to get water projects approved on state level and it was unsuccessful for many times.

The largest water resource in the Umatilla basin is the Columbia River, which has an annual discharge of 7,790 m3/s. The Columbia has been extensively developed over the past sixty years for flood control, hydropower production, irrigation, and navigation (Hamlet and Lettenmaier, 1999). Sixty dams exist in the Columbia River watershed, which generate more than two-thirds of the electricity for the Pacific Northwest via hydropower (Houston and Whittlesey, 1986). The US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) own and operate the majority of dams on the Columbia River and the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) markets the power produced at wholesale value in Morrow and Umatilla Counties (Ochoa, 2012) via local non-profit energy cooperatives and for-profit energy providers. In the recent decades, ecological considerations, such as the preservation and enhancement of threatened salmon populations have taken precedence in the management of the river’s water resources (Ochoa, 2012). A thriving salmon population is an important cultural resource for The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) (Quaempts, et al. 2018).

Three major river systems make up the Umatilla Basin:

The Umatilla River (100 miles in length)

The Walla Walla River (61 miles in length)

The Willow Creek (79 miles in length)

All three rivers flow from their headwaters in the Blue Mountains to the Columbia River. The Umatilla River drainage and the northern portion of the Walla Walla River drainage are mostly in Umatilla County. The southern portion of the Walla Walla River drainage is in Washington State. The Willow Creek drainage is mostly in Morrow County, the confluence with the Columbia River is in Gilliam County. These rivers support bull trout, Redband trout, Pacific lamprey, fall and spring Chinook salmon, Coho salmon and steelhead. The Umatilla Basin is characterized by irrigated agriculture at lower elevations, with grazing and timber lands at higher elevations. Elevations within the basin range from less than 300 feet at the Columbia River, to above 6,000 feet at the highest peaks of the Blue Mountains. Agricultural land, both dryland and irrigated, comprise the major portion of the basin. Crops include onions, corn, dry and green peas, and potatoes. The basin also contains many fruit orchards (cherry, apple, peach, pear) and vineyards. In 1990 DEQ declared the Lower Umatilla Basin a Groundwater Management Area because nitrate-nitrogen concentrations in many area groundwater samples exceed the drinking water standards for nitrate (10 mg/l). The groundwater area covers the lower portions of the Umatilla and Willow Creek drainages. There is a Pesticide Stewardship Partnership in the Oregon portion of the Walla Walla River drainage

Threats

Unexpected changes and disturbances can threaten consistent availability and quality of shared natural resources (e.g., water, energy, and land)

Threats vary in origin, scale, and magnitude and affect Resiliency of Food, Energy, and Water sectors in local communities. Over time, water, energy, and land resources impaired by threats could make it challenging for our local food, energy, and water sectors to absorb unexpected changes and retain function.

Below is the list of some chronic and acute threats:

Urban growth

Policy changes

Ground Water depletion

Water quality depletion

...

Ecological -Hydrological-climatic disturbances

Socio-economic changes

Adoptation Strategy

How can we increase the capability of communities to visualize food, energy, and water interdependencies over space and over time to create proactive planning strategies that engage all stakeholders and all sectors in together developing solutions?

How do we stop the day by day and sometimes even minute to minute chase for water, energy, and food efficiency and help these communities think about long term systemic changes to the critical natural resources and even use prior knowledge to fuel all of the solutions.

InterACTWEL is a computer-aided decision support system that is being developed to empower land, energy, and water managers and even food producers to envision and plan towards a resilient future for their local communities.

The decision support system is being designed to help local communities plan for range of environmental disturbances for example extreme floods, droughts, ground water declines, and even changes to agricultural or environmental policies.

Connected communities have much better chance of being prepared to manage risks posed by uncertain future. How we manage our water, energy, and land resources as threats increase, is going to be critical and insuring how resilient we are in the long run as the future unfolds.

Coordination among stakeholders is especially critical when resource availability and quality is threatened. Stakeholders may include those whose livelihoods depend on food and energy production, as well as availability of water for consumptive uses (e.g., industry, agriculture, drinking water) as well as non-consumptive uses (e.g., fisheries, ecosystem maintenance, recreation, navigation, hydropower, cultural preservation). Food-Energy-Water (FEW) actors often include farmers, tribes, water managers, dam operators, industries, recreationalists, government agencies and environmentalists. InterACTWEL is a computer-aided decision support tool that empowers FEW actors to envision and plan towards a resilient future for their local communities. Unlike other tools that focus on the short-term decision-making, InterACTWEL in a long-term planning tool that help communities be more resilient to changes that they do not have control of, such as a severe water restriction or changing state laws. Whenever there is an environmental disturbance (e.g., extreme floods, droughts, groundwater declines, fish diseases) or when there are new agricultural or environmental policies, FEW actors can use InterACTWELs intuitive interfaces to examine how these factors will affect their goals, operations and livelihoods. The scientific models in InterACTWEL allow individual actors to identify potential adaptation strategies from a wide range of management choices available to them, while also enabling them to learn about how their decisions affect other FEW actors. With InterACTWEL local communities of FEW actors can increase their overall capacity to adjust their operations through time, for uncertain and adverse stresses affecting the environment or the economy. Anyone can use and access InterACTWEL; the data-secure tool is easy to navigate and can run on either a desktop or mobile application. How it works: InterACTWEL goes well beyond just being a web-based platform to share data and information among FEW actors in a local region. The system contains advanced scientific models and interactive optimization algorithms that can quickly synthesize and leverage the collective wisdom of FEW actors. The algorithms help identify potential adaptation strategies, while also meeting environmental, economic and social sustainability goals.